Raad Shakir

While visiting various countries and looking at neurology practice, I became convinced that the fundamentals are by and large the same. The work neurologists perform in their daily practice is duplicated across the world. I have been privileged as WFN president to be able to attend annual congresses of neurological societies in countries as diverse as China, Macau, India, Sri Lanka, Morocco, Egypt, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Albania (Figure 1), Chile and most recently Norway (Figure 2).

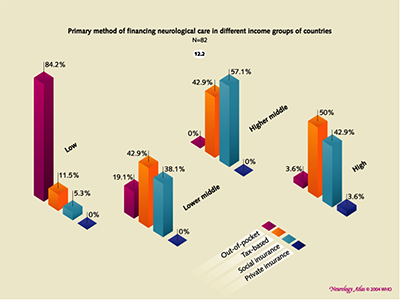

The diversity is clear. As the health care systems are so different, it makes one wonder if the practice is therefore affected. There are noticeable differences. The organization of patient’s care is either through state, insurance funding, self-pay or on many occasions a combination. As we know from the Neurology Atlas 2004, the lower income economies have a much higher probability of self-pay provision of care than in richer countries (Figure 3). This puts a huge slant on the availability of neurological care and the difficulty in accessing specialist opinion.

Figure 1. Left to right. Antonio Federico (Sienna Italy), Jera Kruja President Albanian Society of Neurology, Raad Shakir (WFN President), Mira Rakacolli Dean Faculty of medicine Tirana University.

If we start with numbers of patients seen by a neurologist in a working day, in many instances, there are no outpatient appointment systems and patients appearing in clinics have traveled long distances. On many occasions, this involves relatives bringing patients and expecting hospital admission. This may well be needed on many occasions, as the neurological status is so advanced, patients need to have inpatient care. Neurologists and neurology trainees work in crowded clinics making basic decisions, and the more detailed assessments will be carried out when a patient is admitted to a hospital bed. This practice is the only way to cope with large outpatient loads, which would be unthinkable in other settings. The reasons are lack of neurologists and facilities for a more time-requiring approach at outpatient clinics. The other perhaps related reason is the centralization of neurological care in big cities. Neurologists in such settings make quick decisions on the facts as they see them. In nearly all patients, there are no written referral letters of background information; it is quite admirable to see real coalface practice with decisions made on few available facts as they present.

Figure 2. Left to right. Anne Hege Aamodt President of Norwegian Neurological Association, Olga Bobrovnikova Renowned Pianist, MS sufferer and European Brain Council Ambassador, Raad Shakir WFN President, Hanne F Harbo Head Norwegian Brain Council. (photographer, Lise Johannessen Norwegian Medical Society).

In other settings, there is huge utilization of day care facilities for performing a battery of investigations within a working day. In such settings, the care is supplemented by the availability of infusion suites, EEG/video telemetry, procedures such as lumbar punctures, muscle and nerve biopsies, detailed imaging and neurophysiological assessments, which can be performed within a day care setting. This is only possible in the presence of a well-developed administrative support and the involvement of supporting services such as radiology, laboratory and advanced nursing skills.

The relationship of neurology to general medicine is strong in many settings as the acute care at emergency departments is provided by general physicians, emergency care specialists and in other settings, neurologists are available in the emergency departments for onsite consultation and further care. This has been made more available with the introduction of Hyper Acute Stroke Units (HASUs). In some settings, patients with suspected stroke are brought to emergency departments where they would be assessed by neurologists for their suitability for thrombolysis. This is a huge advance in stroke care and has the other advantage of putting neurology services at the forefront of acute medical care. The increase in the workload requires increasing staff numbers, and this is possible in some settings but not others. The success of thrombolysis treatment in acute stroke depends on pre-hospital and in-hospital health workers. Figure 4 shows the acute stroke team at Oslo University Hospital in Norway (courtesy of Professor Espen Deitrichs).

Figure 3. Bars to the left show that 84.2% of funding of Neurological care in Low income countries is out-of-pocket. Neurology Atlas WHO/WFN 2004.

Many other neurological services are struggling with the new practice due to several factors apart from finance; logistics and the availability of a high-powered ambulance and paramedic services lead many to be behind in their ability to provide modern care. The decision-making process of a paramedic in perhaps the two most important non-traumatic emergencies, i.e. heart attack and brain attack, lead to a major lack of highly trained individuals for this type of work. In many countries, this shortage of staff is leading to inferior care.

The multidisciplinary approach to care with integrated multispecialty teams in acute care delivery with availability of interventional neuro-radiologists is limiting the ability for neurology to deliver. In many instances, the availability of endovascular treatment of acute stroke is severely limited by lack of facilities. Using telemedicine in some locations has made a great difference in acute provision of neurological care. Acute thrombolysis is being achieved utilizing telemedicine in some locations.

Figure 4. The Pre and In hospital acute stroke team at Oslo University Hospital in Norway (courtesy of Professor Espen Deitrichs).

Photo: Fundamentals_fig5.jpg

The care for neurological patients with long-term needs is crucial, and this is not really available unless there is some sort of health care system, which allows regular follow-up services. In many countries, this is possible but in others it is not. The recent WHO executive board resolution on epilepsy on Feb. 2, 2015 (http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB136/B136_R8-en.pdfs) is a good example on the lack of neurological long-term care and the continued existence of a massive treatment gap. This declaration should be translated to actual on the ground care provision. Continued support for conditions such as epilepsy, parkinsonism, dementia, multiple cclerosis, migraine and genetically determined conditions and many others remain woeful. The WHO can inform governments of the availability of “cheap” anti-epilepsy drugs as an example, but neurologists should aim to provide optimal up to date care for their patients. The premise that some treatment is better than nothing, although understandable and reflects current status, is not an ultimate goal to aim for. Neurologists should endeavor to put brain health at the top of the political agenda. However, we are delighted that the WHO executive has put brain health at the top of the agenda as it aims to reduce the treatment gap when, as an example, we know that seven out of 10 patients with epilepsy do not receive regular medication at all. I am sure that I speak of behalf of all neurologists who would not accept second- or even third-tier level of management for their patients, but would approve of the WHO executive declaration as a first step in the right direction.

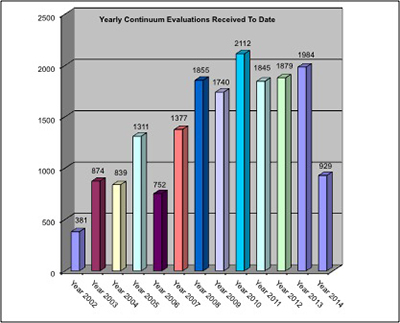

Figure 5. CME Continuum utilization in 45 countries up-to August 2014. WFN six monthly report August 2014. Helen Gallagher WFN CME coordinator.

Returning to the fundamentals of neurology, it is my conviction that neurologists from all over the world offer their services in basically the same manner if given equivalent circumstances. This is clear from observing training programs and the eagerness of young trainees to learn. The knowledge base is nearly universal. The WFN is in a position to see this when we administer the American Academy of Neurology Continuum CME program to 45 countries. This is happening today in war-ravaged countries and in those with low income to the degree of the existence of real malnutrition. The evaluations sent by the WFN tutors are a shining testament to the eagerness and the excellent performance of trainees from various backgrounds across continents (Figure 5).

To end on a positive note, neurology is prospering and need continuous momentum to keep brain health at the top of the health agenda of decision-makers.

Raad Shakir

London UK