Ryuji Kaji MD, PhD

In his 2010 inauguration speech as the president of World Federation of Neurology (WFN), Prof. Vladimir Hachinski conveyed a message: “Asia has more than 60 percent of the global population, yet in some areas, the education of neurology to young neurologists does not keep up with the patients’ needs of neurological care.” He organized the Asia Initiative as a part of WFN to bring attention to this region. As the chair of this initiative, I have met many Asian neurologists and have begun to realize that there are unique problems that require attention from the rest of the world.

The 14th Asian & Oceanian Congress of Neurology was held in March in Macao, China. This is an official meeting of Asian Oceanian Association of Neurology, whose history dates back almost half a century ago. Charles M. Posner, a WFN representative, toured the Asian and Oceanian countries and challenged local neurologists to form an association that would promote and foster the advancement and exchange of information within the area. In response, Shigeo Okinaka, then the executive of Japanese Society of Neurology, invited the region’s neurologists to a planning meeting in Tokyo. This gave birth to the Asian and Oceanian Association of Neurology (AOAN) on June 26, 1961. Its official meeting, Asian & Oceanian Congress of Neurology (AOCN), had been held every four years until the current 14th meeting in China, which followed the 13th meeting in Melbourne in 2012 by two years. There was uncertainty over the financial and scientific outcomes of this short-interval meeting, but thanks to the dedication of the Hong Kong Society members, it became an unprecedented meeting with the largest number of international participants ever. Its surplus funds should significantly contribute to the activities of AOAN, chaired by Dr. Man Mohan Mehndiratta from India. The next AOCN will be held in 2016 in Malaysia.

On March 4, there was a plenary session on “Special Issues in Asia,” in which three speakers spoke. Prof. Chong-Tin Tan from Malaysia gave a talk on education in Asia. He serves as the editor of Neurology Asia, the official journal of AOAN and Association of Southeast Asian nations Neurological Association (ASNA). He pointed out that Asia accounts for 60 percent of the world population, but less than 20 percent of neurologists in the world, and stressed that education is the key to development of neurology in Asia. Next, Dr. Li-Ping Liu from China emphasized rapidly advancing frontiers of neuroscience research in China. At the last of this session, I gave a talk on neurology service in Asia. Asian countries are rapidly exploding in population and economy. Some are facing unique problems not experienced in other regions1.

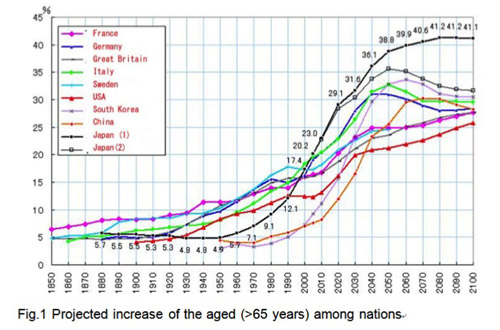

Figure 1. Projected increase of the aged (>65) populations among nations.

Adapted from Current Status and Predictions for an Aging Society with Fewer Children, Japanese Ministry of Education, Sports, Culture, Science and Technology (with permission).

Figure 1 depicts the projected increase of the population over 65 years among nations. While Western countries have a linear increase of the aged over years, Asian countries (Japan, Korea and China) have S-shaped curves indicating a steep surge of the aged population during 2000-2020 (Japan) and 2020-2030 (Korea and China). India will probably join this group by the end of this century.

Japan is the first to be exposed to this surge, and medical needs for the aged people are highlighted. Among these, neurological disorders such as stroke and Alzheimer’s disease came to the forefront. For instance, the number of stroke survivors has steeply increased from 1.7 million in 2000 to 2.8 million by 2013. Stroke was the No. 2 killer in the 1970s, but it is currently the fourth, following cancer, heart disease and pneumonia. Although the number of stroke attacks is six times as frequent as heart attack, it has largely become non-fatal, although it typically leaves disabilities; two- thirds of the patients are unable to return to pre-morbid activities.

From the global point of view, stroke is the second leading cause of death after ischemic heart disease, with an estimated 5.5 million people dying from stroke every year worldwide. Two thirds of these deaths occur in countries with limited resources2. Approximately 80 percent of patients survive the acute phase of stroke, but are left with varying degrees of chronic disability.

Not only the number of deaths, but also the quality of life after stroke is an important aspect. Disease-adjusted life years (DALYs) are defined as number of years of healthy life lost by disease3. They reflect the impact of a disease in the aging societies.

Figure 2. Disease-adjusted life years (DALYs) of neurological diseases with respect to nation’s income status. Data from WHO (2005).

Figure 2 shows DALYs among various neurological diseases with respect to the economic status of a nation. Stroke is more important than Alzheimer’s disease, because many Asian nations are still in the state of low-middle income by World Bank Criteria. Japan had been among those with limited resources with high mortality of stroke, but her economy grew up in a short period to high income state, and other Asian nations should follow this path.

The drop of stroke mortality in Japan is due to change in diet, western lifestyle and the efficient social health care system. However, the main factor is the control of hypertension by medication, which decreased the number of fatal massive hemorrhages3. The impact of thrombolytic therapy is limited, rather increasing those disabled by preventing stroke deaths4.

The expense related to caring for stroke survivors is now exceeding $25 billion (U.S. dollars) per year in Japan. Now the Japanese economy is revolving around those aged patients and their care. In fact, a major diaper maker saw sales of adult diapers outpace infant diapers. Stroke centers with staff dedicated to thrombolytic therapy are urgently needed, and we are investing effort into increasing awareness of stroke among Asian people. Educating health professionals in neurology is the Asian Initiative’s first priority.

The roots of neurology lie in Europe and this specialty matured in the U.S. Asia has its own priorities in coping with neurological diseases. In this regard, I propose “autonomy” as a key word for activating regional neurological organizations. We need a forum to discuss the problems in each region, and to provide unique educational opportunities for neurologists, general practitioners, allied health professionals and the patients. With these aims in mind, the WFN has decided to make the best use of the existing regional neurological organizations such as AOAN to fulfill its mission.

Another key for success would be “synergy”. Symposia and workshops were held in collaboration with international organizations such as the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) and the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (IFCN). These joint activities provided the financial support for the meeting and increased the attendance. The event also helped the supporting organizations increase their visibility. I hope that the March 2014 meeting in Macao becomes a model for the future meetings in Asia, and the meeting will serve as an equivalent to EFNS, ENS or American Academy of Neurology meetings.

Alzheimer’s disease is a little harder to tackle. Traditionally, Asian people had a large family, three generations living together. The aged people lived with younger family members. In my childhood in 1950s, the aged are naturally thought to have memory loss to some degree. It is still a virtue that children respect and take care of the parents by Asian standard. Re-appraisal of this system in the face of increasing Alzheimer’s disease might be a solution for countries with limited resources. For the aged, it would be appropriate to prepare for the intellectual decline.

Steve Jobs, the former CEO of Apple Computer, gave a speech at the commencement at Stanford in 2005. Facing the recurrence of cancer, his message on coping with imminent death might be a hint: in the morning he thought about his life as if ending in the evening. Whenever he thought the activities of the day were not what he really wanted to do, he changed his life. These were actually the words of the old Chinese philosopher, Confucius (551–479 BC), which he probably was familiar with. Alzheimer’s disease is still unpreventable and incurable probably for the next decades to come. “Think Oriental” might be the key for the societies and the neurological community in the world.

References

1. Kaji R Asian Neurology and Stroke (Perspectives) Neurology, in press

2. WHO, W. Neurology Atlas, (2003).

3. Murray, C.J. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2197-223 (2012).

4. Kubo, M. et al. Secular trends in the incidence of and risk factors for ischemic stroke and Its subtypes in Japanese population. Circulation 118, 2672-8 (2008).

Kaji, is the Chair, Asia Initiative, World Federation of Neurology, Professor and Chairman, Department of Neurology, Institute of Health-Bioscience, Tokushima University.